The journey of your diamond begins a billion years ago a hundred miles deep in the earth’s crust. The pressure is so intense, 45,000 times the pressure at sea level, that atoms of carbon crystallize into diamond, the hardest material on earth.

The diamonds we admire today were carried to the earth’s surface in volcanic pipes of molten kimberlite that pushed through solid rock at 30 kilometers per hour. The last diamond-bearing eruption was 100 million years ago: every diamond deposit mined today is older than that.

With that difficult journey through the earth’s crust, it’s not surprising that diamonds are rare. On average, miners must move 250 tons of earth to find a single carat of diamond. All the gem-quality diamonds ever mined would fit in one London double-decker bus. That’s why mining companies are willing to invest billions of dollars in setting up mines in crazy remote places like under a lake in the Canadian arctic, in the middle of the desert in Botswana, or on the frozen tundra of Siberia.

Diamonds were first discovered in India in the 4th century BC. India remained the most important source of diamonds for millennia until diamonds were found in Brazil in the 1720s, North America in the 1840s, and Africa in the 1860s.

The Kimberly Mine in South Africa was the first true large-scale diamond mining operation. Founded in South Africa in 1888, De Beers, a company that dominated diamond production and distribution for a century after that, now produces and sells only about 30 percent of the world’s diamonds, about the same as Russian mining giant Alrosa.

The diamond world has become a lot more transparent too. Today, you can buy responsible diamonds traced through every step from the mine to your finger with new diamond provenance certification. This goes beyond the Kimberley Process to provide a chain of custody for each individual diamond so you can know the story of your exact stone.

At RockHer we are partners in Lipari Mineraçao, which operates the largest diamond mine in South America, the Braúna mine in Brazil. We are proud to support the mine’s efforts to benefit its community and provide jobs, economic security, and productively reclaimed land for the people of Nordestina in Brazil. The mine is a showcase for responsible mining principles, so well run that it regularly opens its doors to the local community so that everyone can see first-hand how it operates. The Braúna Mine is the first diamond mine in South America that has been developed from a kimberlite deposit, the primary source rock of diamond.

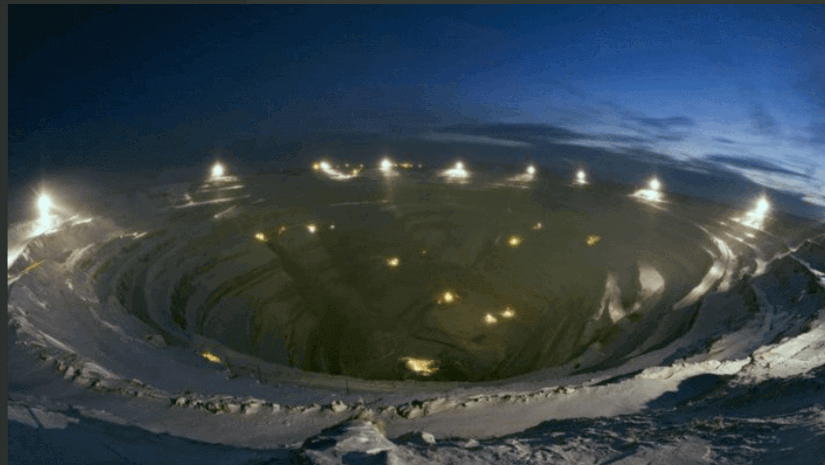

Alrosa’s Jubilee Mine in Russia

Alrosa’s Jubilee Mine in Russia

The World’s Biggest Diamond Mines

Today, Russia is the top diamond producing country, followed by Botswana, Canada, Angola, and South Africa. There are four basic kinds of diamond mining: alluvial mining, pit mining, underground mining, and marine mining.

Compared to most of the mining industry, diamond mining has a relatively small environmental footprint because no chemicals are used. Many operations are working on projects to move towards carbon-neutral status. (De Beers is working on technology that can sequester carbon in decommissioned mines.) According to the Diamond Producers Association, the carbon footprint of a one-carat polished, natural diamond is smaller than that of most CVD synthetic diamonds of similar size.

In addition, diamond mining is a major source of employment in many developing nations around the world without other options for employment.

Alluvial diamond mining occurs in riverbeds and beaches, where thousands of years of erosion and natural forces such as wind, rain, and water currents wash diamonds from their primary deposits in kimberlite pipes to beaches and riverbeds. Some alluvial deposits are from long-ago rivers.

Mining alluvial deposits can be as simple as panning through gravel in a stream and as complex as larger projects that divert rivers to expose diamond-bearing gravels. Small-scale diamond mining supports 1.5 million artisanal miners and their families in Africa and South America, who uncover 15% of the world’s diamonds. Large scale alluvial diamond producers include Russia and the Lulo Diamond Project in Angola.

Open pit diamond pipe mining is the most common way to recover diamonds directly from kimberlite pipes. Blasting loosens the diamond bearing rock and huge earth-moving machines load the ore into huge 300-tonne trucks that take it to a diamond processing plant.

Because most of the open pit diamond mines are in remote locations, they are fantastically expensive to operate: all the workers need to be flown in, housed and fed. Jwaneng Mine in Botswana and Jubilee Mine in Russia are the largest two open pit diamond mines.

Botswana, which has risen out of poverty, has become a showcase of democracy and development thanks to diamonds, which account for 71% of export revenue, 16% of government revenue and 16% of the gross domestic product. The government of Botswana owns 15% of the De Beers group and 50% of Debswana, the De Beers/Botswana joint venture, ensuring that the profits from its diamond resources benefit the country.

Diavik Mine in Canada is now underground

Diavik Mine in Canada is now underground

Occasionally a diamond mine is productive enough to continue as an underground mine after it becomes too deep to be effectively pit mined. The Cullinan Mine in South Africa, which was discovered in 1902, the Diavik Mine in Canada, and the Argyle Mine in Australia are three mines that are rich enough to remain profitable despite the high cost of underground mining.

Marine diamond mining extracts diamonds from the ocean floor using special mining ships. Horizontal marine diamond mining uses a crawler to suck gravel from the ocean floor to the surface via flexible pipes, while vertical diamond mining uses a large, ship-mounted drill to pull up the diamond-bearing gravel. Namdeb in Namibia operates the largest marine diamond-mining operation.

Diamond processing at Diavik

Diamond processing at Diavik

How Diamond Rough is Processed

Once diamond bearing ore and gravel is collected, huge processing plants sort through the ore to find the diamonds. Many of these processing plants are completely automated.

First, all the rock is crushed into smaller, more manageable pieces measuring no larger than 150mm. A secondary crusher, known as a roll-crusher, may also be used to reduce the size of the ore even further.

The ore is then scrubbed to remove loose excess material. Material smaller than 1.5mm is discarded because it is too costly to extract diamonds from such a small piece of ore.

The diamond bearing ore is mixed with a solution of ferrosilicon powder and water to create a slurry with a specific density. This solution is fed into a cyclone, which tumbles the material and forces a separation by density. This is similar to panning, which concentrates heavy pieces of the ore, which may contain diamonds. Materials with a high density sink to the bottom, which results in a layer of diamond rich concentrate.

Here, the concentrate is then screened to separate out the diamonds using magnetic fields to remove metals, X-ray luminescence and crystallographic laser fluorescence. One of the oldest methods of screening is a greased belt: diamonds stick to oily substances.

The diamonds collected in the recovery process are cleaned in an acid solution, washed, weighed and packaged in sealed containers for transport.

In accordance with the Kimberley process, these containers are sealed with a tamper resistant seal, numbered on site, and a certificate of origin is issued.